Scenes of life in early-twentieth-century Little Manila, the...

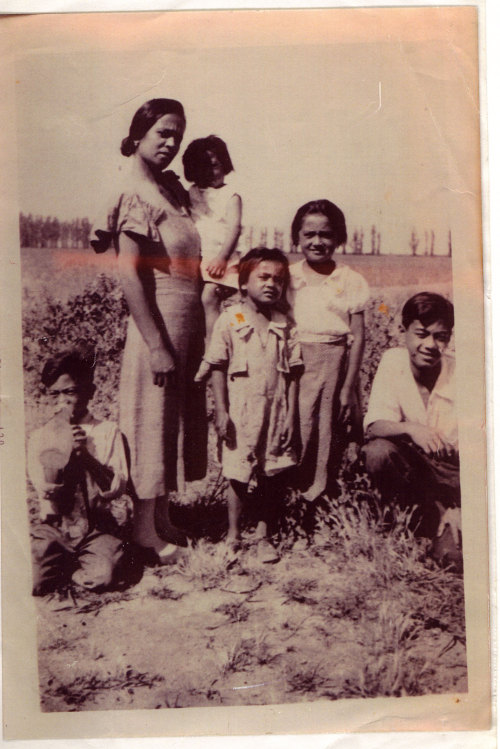

The Cano family in 1936 in Terminous Tract near Highway 4. Courtesy Phyllis Ente.

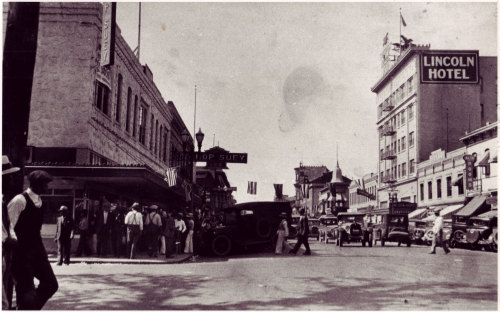

The northern end of Little Manila, at El Dorado & Washington Streets, late 1920s. Photo by Frank Manaco, courtesy National Pinoy Archives.

Camila Labor, a native of Hunundayan, Lete, married Leon Carido, a native of Bohol, in 1932 in Stockton. Courtesy Filipino American National Historical Society.

Pinoys gather in front of the Fukuyoka Hotel at 228 S. El Dorado St. in the late 1920s. Courtesy Filipino American National Historical Society.

Pinoys gather to play cards in the campo after a long day in the fields, 1930s. Courtesy Filipino Oral History Project.

Helen Nava is crowned queen of the Filipino community of Stockton in 1942. Courtesy Magdael family collection.

Scenes of life in early-twentieth-century Little Manila, the Filipino American community in Stockton, California. From Little Manila Is in the Heart by Dawn Bohulano Mabalon (Duke University Press, 2013).

"Today the feminist-as-lesbian is everywhere and nowhere. Sometimes she appears in classroom...

"Today the feminist-as-lesbian is everywhere and nowhere. Sometimes she appears in classroom discussions when students are asked to describe their understanding of feminism. At other times she appears in movies and television shows about modern young women and in magazine and newspaper articles about the apparent demise of feminism in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. And sometimes she appears in the work of scholars eager to differentiate queer from lesbian and lesbian feminism or one kind of feminist theory from another. This everywhere and nowhere characteristic of the feminist-as-lesbian is itself a sign of her spectrality: she floats from discursive domain to discursive domain, present yet without substance; she is necessary to the discussion or representation but never its subject. The spectrality of the feminist-as-lesbian works in complex ways to screen us from the multiple ways in which the various feminisms of the early second-wave era challenged the postwar American social and cultural hegemony, and in her continuing hypervisibility, the figure also reminds us that those challenges are not yet over."

From Feeling Women's Liberation, by Victoria Hesford (Duke University Press, 2013).

"Riot Grrrls' display of Hello Kitty, by the way, predates...

"Riot Grrrls' display of Hello Kitty, by the way, predates Sanrio's appropriation of punk, beginning with its 2003 product line and continuing sporadically thereafter. Sanrio's punk line designs run in black, with red or pink, often with Hello Kitty variously winking, playing a guitar, wearing accoutrements such as a safety pin, in short, red tartan plaid skirt, wearing a headband, with a pink Mohawk haircut, with extreme black eye makeup. Sometimes Hello Kitty's characteristic bow has been traded for a black ribbon, a red tartan plaid ribbon, or a skull-and-crossbones decoration, each of which shows Sanrio playing with punk as a design motif. Moreover, it is not only design elements, but items themselves that go into the punk line. Thus, Sanrio's punk line includes accessories to a punk lifestyle (or at least, mode of dress) — socks, hair accessories, buttons, pins, bikini underwear, and body-skimming tank tops — as well as the standard Hello Kitty fare of school supplies, T-shirts, and plush dolls. Although punk women such as Riot Grrrls may or may not choose to purchase these Sanrio products for which they served as inspiration, the line accommodates those who see punk in terms of sheer style. The borrowings and quotations go in both directions, from company to street and back again."

From Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty's Trek across the Pacific by Christine R. Yano (Duke University Press, 2013).

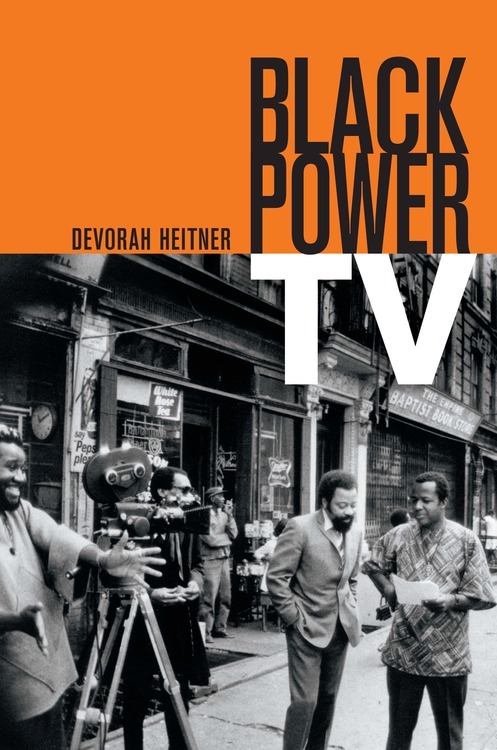

Even as others were dismissing TV as a vast wasteland, African Americans seized the opportunities...

Even as others were dismissing TV as a vast wasteland, African Americans seized the opportunities created by social crisis to create and retool representations of themselves in an increasingly influential medium. Social crisis created the conditions of possibility for a momentary war of position in which emergent Black radicalism could be injected into the media flow, helping both audiences and media makers reimagine what TV could mean. In an era of multiple and contested ideas about Black liberation, these shows portrayed Black communities as discursive environments where Black nationalist ideas had permeated and were debated, and a place where parents on welfare, business owners, teachers, war veterans, police officers, and high school students held and articulated strong political beliefs. The programs represented new cultural practices and legitimized activism by documenting struggles against school segregation, university discrimination, substandard housing, and public officials' lack of accountability to Black constituents. Programs like Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant and Say Brother countered the invisibility of Black artists by showcasing little-known local performers alongside national acts. The history of these programs shows that local television, as well as national television, offered a crucial set of possibilities for Black viewers. Examining local television, especially in urban areas, is crucial to understanding the possibilities for African American television, as the majority of African Americans live in urban areas of the United States.

Letters such as the following one, from an African American viewer of Soul! (writing to protest the cancellation of that show), typified the transformative experience that these programs offered to Black viewers, and demonstrates how powerfully these viewers appreciated the role of these programs in opposition to mainstream television. On May 5, 1969, Carol E. Walker wrote:

“When TV was completely lily white and had nothing to offer in the line of the Black expression of life, we weren't completely conscious of the whole realm of what we were missing … but to suddenly have a program that we can identify with completely and enjoy to the fullest, and then for it to be taken away leaves an awful void… . TV really never was for me before; and now that three or four hours of viewing per week are for me, I just "Eat them up" with enjoyment.”

The letter closes by describing African American broadcast programming as a right, not simply a luxury or indulgence. "In my opinion," Walker writes, "Soul! is too relevant to the social viewing needs of a group of minorities of the New York area as large in number as we are, to be taken away." This letter writer, after only a year of seeing Soul!, recognized television as a crucial realm for African American self-expression. Her recognition of "social viewing needs" shows how Soul! (and other programs) created a culture of active viewing and interactivity.

From Black Power TV, by Devorah Heitner (Duke University Press, 2013)

"Noise performance breaks down the public scene of live...

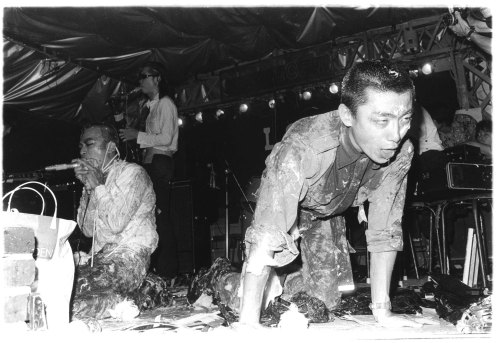

Hijokaidan, circa 1979. Photo by Jibiki Yûichi.

Masonna at Festival beyond Innocence, Osaka, 2012. Photo by Kumazawa Telle.

Mikawa of Incapcitants. Photo by John Spencer

Incapacitants and crowd at No Fun Fest, 2007. Photo by Michael Muniak.

"Noise performance breaks down the public scene of live music audiences into their subjective encounters with extremely high volume. The only choices are to stay to feel it or to leave. At the beginning of many Noise performances, the audience splits in two: in an instant, some press closer to the stage and the speakers, and others retreat to the back of the room. Listeners must decide, almost immediately, whether they can tolerate the overwhelming volume. Those who remain must find a way to appreciate this sound—to construct some valuable framework of personal experience through it—or they are forced from its presence. Unlike the nuanced contours of a good live sound mix, which brings a crowd together in a shared public atmosphere, Noise concerts flatten the space with overwhelming loudness. Extreme volume divides the common social environment of music into individual private thresholds of sensation. A really good Noise show confuses you, separates you from your acquired knowledge, and makes you wonder what's going on. It is easy to know that a Noise performance will be loud, but successful Noise performances still feel shockingly and unexpectedly so."

From Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation by David Novak (Duke University Press, 2013).

From Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation by David Novak (Duke University Press, 2013).

“A sheet of paper flutters against the door of a dive bar on a deserted downtown street in...

“A sheet of paper flutters against the door of a dive bar on a deserted downtown street in a mid-sized Northeastern city. The 8.5 × 11 flyer, crudely designed with hand-drawn black-and-white text, announces a live Noise show featuring two performers from the area, as well as a Japanese artist on a brief tour of the United States. Inside the bar, two distinctly separated groups of people are clustered in the small space. On one side, a motley group of college-age stragglers are scattered around the room, some standing directly in front of the pa, others leaning against the walls. On the other side, some regulars are huddled together wondering what's going on, trying to get as far away from the amplifiers as possible, and obviously ruing the invasion of their local watering hole by these ear-blasting misfits. The Japanese performer is climbing up a pillar in the center of the room, directly above a tableful of random electronic gear that has filled the room with screeching feedback for the last fifteen minutes. He leaps from the pillar onto the table, falling backward as his equipment scatters across the room, and slowly stands up as the Noise fans applaud and roar their approval. In the sudden silence, someone sitting in the back of the bar shifts his weight on his stool, swiveling over and cupping his hand against his mouth to shout: "We don't understand what the hell you're doing!" One of the local performers looks up from another small table, where his gear is already half-plugged together in preparation for the next set, shoots a grin at the Japanese performer, and yells back: "It's Noise—you're not supposed to!"”

From Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation, by David Novak (Duke University Press, 2013)

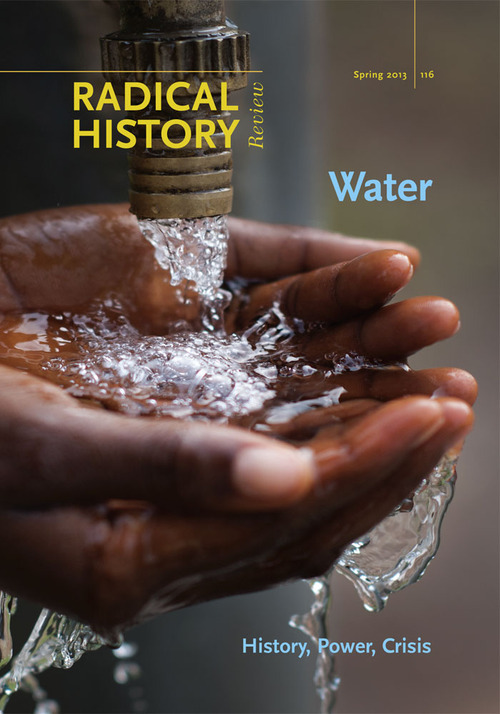

“Indeed, climate scientists tell us that dramatic shifts in weather, either too hot or too...

“Indeed, climate scientists tell us that dramatic shifts in weather, either too hot or too cold, too wet or too dry, will become commonplace, creating conditions where the struggles over and control of water will emerge as one of the central political, ecological, and public health issues of the twenty-first century.” - Excerpt by David Kinkela, Teresa Meade, and Enrique Ochoa, editors, from “Water,” in Radical History Review 116, Spring 2013

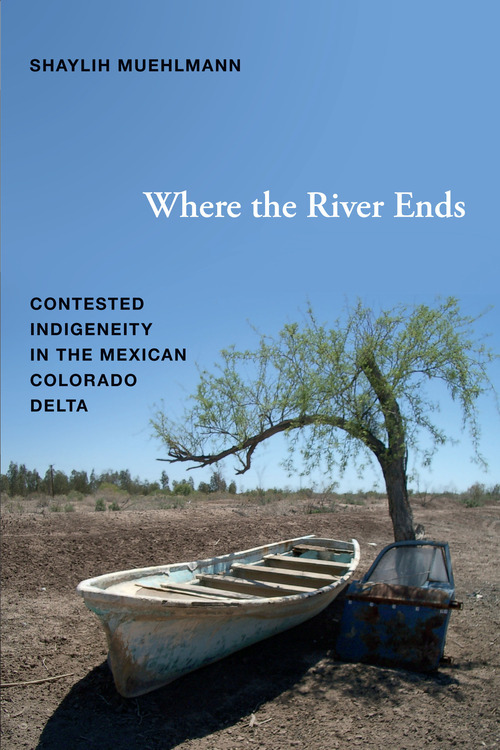

“We are here. We eat, we dance, we fish. Here we are and we still live. No eramos,...

“We are here. We eat, we dance, we fish.

Here we are and we still live.

No eramos, somos.” (It's not that we were, we are.)

—Don Madeleno

Don Madeleno often repeated the refrain ''We're still here.'' The first time I heard him say this, I interpreted it as a triumphant declaration of survival. In this instance, Don Madeleno was narrating the history of the Cucapá people in the delta: a history of war, conquest, disease, water scarcity, the criminalization of fishing, and the rise of the narco-economy. After everything his people had experienced, they were still there carrying on with their lives.

I heard Don Madeleno use the phrase in this sense on many other occasions: in interviews, at festivals, and in informal conversations. Because it was part of his personal narration I was struck when I first heard him use the phrase in a much more literal sense in the context of maps. Every so often I would bring Don Madeleno a map of the delta from books or archives to elicit his reactions to these representations of the land he knew so well. Every time I brought him a map we went through the same routine: he would look over the page slowly and meticulously and start pointing to all of the places it was missing. He would comment on whether or not the map showed the Cucapá village, the fishing grounds, and the Sierra Cucapá. He would also bring up the places that were almost always missing—Las Pintas, Pozo de Coyote, and a dozen other sites important to Cucapá history. Then Don Madeleno would irritatedly declare, while pointing at the absent places, ''Estamos aqui'' (We are here). Once or twice he went on to emphasize his point by saying, ''Somos aqui'' (We are this place).

From Where the River Ends: Contested Indigeneity in the Mexican Colorado Delta, by Shaylih Muehlmann (Duke University Press, 2013)

Photos of Afro-Brazilian musicians in the early twentieth...

The Batutas, ca. 1923. Courtesy Acervo Instituto Moreira Salles, Coleção Pixinguinha.

Donga (second from left), Pixinguinha (second from right), and friends at the port. Courtesy Acervo Instituto Moreira Salles, Coleção Pixinguinha.

Alfredo José de Alcântara. Courtesy Acervo Instituto Moreira Salles, Coleção Pixinguinha.

Grupo Caxangá: Pixinguinha is standing with a flute at the far left; Donga is seated with a guitar to the far right. Courtesy Acervo Instituto Moreira Salles, Coleção Pixinguinha.

Photos of Afro-Brazilian musicians in the early twentieth century. From Marc A. Hertzman's Making Samba: A New History of Race and Music in Brazil (Duke University Press, 2013).

People Get Ready "Avoiding artificial separations," as William Parker writes in the liner notes...

People Get Ready

"Avoiding artificial separations," as William Parker writes in the liner notes to his Curtis Mayfield project cd, "is the key to understanding the true nature of the music." So, people get ready. Get ready for the collapsing of historically institutionalized categories. Get ready for idiosyncratic admixtures of categorically disparate forms of cultural expression. Get ready for "inside songs" that move with ease into the music's outer regions. Get ready, as Henry Threadgill might have it, to learn (really learn) how to talk about (and listen to) "everything," and to do so with genuine curiosity, attentiveness, and openness. Parker, again: "Curtis Mayfield was a prophet, a revolutionary, a humanist, and a griot. He took the music to its most essential level in the America of his day. If you had ears to hear, you knew that Curtis was a man with a positive message—a message that was going to help you survive." If the future of jazz is now, as indeed we believe it is, then the pertinent question, to rephrase Parker, is whether, in fact, we have the "ears to hear."

From People Get Ready: The Future of Jazz is Now!, edited by Ajay Heble and Rob Wallace

"Perhaps queer theory comes easily to mind here, and in many other studies on Asian Americans, to...

"Perhaps queer theory comes easily to mind here, and in many other studies on Asian Americans, to make sense of how relatively visible middle-class Asian Americans occupy the spaces afforded them by the culture at large because they are, in addition to being in many cases also gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered themselves, structurally so similar with middle-class, professional gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and, to a much lesser extent, transgendered as popularly imagined. That is, both are queer in the sense of belonging and not-belonging in America. They are thus symbols of socioeconomic upward mobility and cultural indeterminacy. As Aihwa Ong observes, Asian Americans have moved away from being perceivable as subjects of a racism that refers to a set of relations determined by structural factors intrinsic to a nation toward being figured as members of an international elite of highly skilled workers that grants them the privilege of being accepted as almost white. They are, according to this thinking, not racial minorities, as this term is commonly understood in the United States and as some out of residual commitment to the politics of the late 1960s want to argue. They are, instead, something fabulously—and dismissively— akin to gays and lesbians in the social position they currently occupy."

From The Children of 1965: On Writing, and Not Writing, as an Asian American, by Min Hyoung Song (Duke University Press, 2013).

If you buy 6 or more books at our Spring Sale you get a free...

If you buy 6 or more books at our Spring Sale you get a free tote bag. But hurry, they are going fast!

We're having a Spring Sale! 50% off all in-stock titles....

We're having a Spring Sale! 50% off all in-stock titles. Head over to our website to shop and save.

Death from Above: Drones and Virtual Warfare in the Af-Pak Theater "The U.S. Air Force has been...

Death from Above: Drones and Virtual Warfare in the Af-Pak Theater

"The U.S. Air Force has been increasingly relying on unmanned aerial vehicles (uavs) or drones, particularly the mq-1 Predator (figure 8.1) and larger mq-9 Reaper (figure 8.2). The first uavs were used in Yugoslavia, where in 1998 the Kosovo war became history's first virtual or postmodern war. The seventy-eight- day campaign achieved its objectives without a single nato combat fatality (Ignatieff 2000). Drones were used again during the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan and since 2004 in the tribal borderlands of Pakistan. During this time they have also been used to assassinate people and bomb vehicles and buildings in several other countries (e.g., Yemen in November 2002). Now, they are "preying" on people and "reaping" death and destruction in Iraq, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

The drones are in use "24/7" over Afghanistan and the Pakistan tribal borderlands. These ghost planes are launched from Afghanistan, but mainly flown by joystick pilots located halfway around the world at air force bases in the United States. As Washington and the military see it, the ideal use of Predator and Reaper drones is to pick off terrorist leaders. Most of the drones are armed with Hellfire missiles or smart bombs, which the pilots can fire with the push of a button once they have spotted targets on their video screens. Killing is just a matter of entering a computer command; to the drone pilot, it is like pushing Ctrl-Alt-Del and the target dies. Ctrl-Alt-Del, also known as the "three-finger salute," is computer jargon for "dump" or "do away with," as in the Weird Al Yankovic song "It's All About the Pentiums": "Play me online? Well you know that I'll beat you / If I ever meet you, I'll Control-Alt-Delete you." The uav pilots "have an almost godlike power. Their job is to survey a place thousands of miles distant (and completely alien to their lives and experiences), assess what they see, and spot 'targets' to eliminate—even if on their somewhat antiquated computer systems it 'takes up to 17 steps—including entering data into a pull-down window—to fire a missile' and incinerate those below" (Engelhardt 2009d)….

The hype and hubris surrounding this technology is immense. The mainstream media has been full of glowing reports on the drones, some of which imply that their use could win the war on terror all by itself, such as a report from April 2009 that the drones were killing Taliban and Al-Qaeda leaders and "the rest have begun fighting among themselves out of panic and suspicion. 'If you were to continue on this pace,' counterterrorism consultant Juan Zarate told the LA Times, 'al Qaida is dead'" (The Week, April 3, 2009, p. 7). In an uncritical 60 Minutes television report on U.S. Air Force drone operations in May 2009, the officer in charge was asked if mistakes were ever made in the drone attacks: "What if you get it wrong?" His response was: "We don't" (cbs Interactive Staff 2009)."

8.1 MQ -1

Predator, armed with Hellfire missile. Public domain photo. Source: http://www.af.mil/photos/media_search.asp?q=predator. Provided as a public service by the U.S. Air Force.

8.2 MQ -9

Reaper landing after a mission in support of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, 2007. Public domain photo by Sgt. Brian Ferguson. Source: http://www.af.mil/photos/media_search.asp?q=predator. Provided as a public service by the U.S. Air Force.

(pp 178-181) This excerpt by Jeffrey A. Sluka

From Virtual War and Magical Death, edited by Neil L. Whitehead and Sverker Finnström (Duke University Press, 2013)

Watch the editors of Mad Men, Mad World discuss the show at the...

Watch the editors of Mad Men, Mad World discuss the show at the Chicago Humanities Festival.

In the early modern period, so the story goes, people loved to talk about death; they relished...

In the early modern period, so the story goes, people loved to talk about death; they relished the opportunity to give the grim reaper his due, commemorating human mortality in ritual, song, and speech. Only in the modern period, historians contend, does talk of death begin to recede. With the post-Enlightenment rise of secularism and waning of religious influence, death became so terrifying that it could no longer be articulated. "When people started fearing death in earnest, they stopped talking about it," Philippe Ariès famously observes of the early nineteenth century, the period in which, for the first time in history, cultural anxieties about death "crossed the threshold into the unspeakable, the inexpressible."

And yet, as the many elegies discussed in this book demonstrate, people did not in fact fall silent in the face of a depersonalized and dehumanized death. Rather they began speaking about the dead in new and increasingly creative ways. Poetry in particular, in response to the social decline of death, concentrated on reviving the dead through the vitalizing properties of speech. At the very moment in history that death merely appears to vanish from the public stage, the dying start manically versifying and the surviving begin loudly memorializing. Even the dead commence chattering away in poetry, as if to give the lie to modernity's premature proclamation of death's demise….

But while this book is not a literary history, it may well be a literary exhumation, an attempt to revive a literary genre allegedly rendered obsolete by powerful new mediums for resuscitating the dead. Implicitly arguing for the continued cultural relevance of poetry in a multimedia age, this book refuses to give up the ghost of poetic language. In my desire to defend and explain the power of poetry, I stand allied with those scholars who see in the elegy not a moribund genre in historical decline but a vital form in aesthetic transformation.

From Dying Modern: A Meditation on Elegy, by Diana Fuss (Duke University Press, 2013)

"And what about Don? The show pulls us toward him because...

"And what about Don? The show pulls us toward him because he only very partially embodies the fantasy of a resilient masculine will-to-power. Paradoxically, Don works as as serial character because again and again he manages to be just one step away from the abyss into which we see him drop in the opening credits; and because the fallen world over which he walks his tightrope feels so palpably real. Don, in other words, is imbued with the sense of an ending, but it is an ending that viewers want to defer. We know Don will fail, but we do not want him to—yet."

From the introduction to Mad Men, Mad World: Sex, Politics, Style, and the 1960s, edited by Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky, and Robert Rushing (Duke University Press, 2013).

"The first lesson, communicated by the sheer number and diversity of items on the list, was that...

"The first lesson, communicated by the sheer number and diversity of items on the list, was that anything can addict. Although no substance or activity was bad in and of itself, any consumer behavior—no matter how necessary, benevolent, or life enhancing it might be when practiced sparingly or even regularly—could become problematic when practiced in excess, or ''for its own sake.'' ''Anything that's overly done is not good for us; if you get excessive with running, it's an addiction,'' remarked Daniel. ''Religion, too—there are people who just have to go to church all the time, and that's an addiction.'' This lesson was confirmed when participants unanimously voted self-help itself into the catalogue of addicting items. The implications were dizzying: if the potential for addiction lay even in the remedies intended to treat it, then where did addiction start and end, and how could it ever be arrested or recovered from?

The second lesson was that anyone can become addicted. An older participant in the group commented: ''Aren't we all born with addictive tendencies, to some degree? For one person, it's shopping; for another person, it's cleaning or working. For me, it's gambling and cigarettes.'' Daniel concurred. ''It seems like addiction or compulsion is in everybody,'' he said. ''Some of us do one thing, and some of us do another—even normal people have addictions.'' Rocky, a nuclear scientist, went as far as to suggest that susceptibility to addiction was a constitutive part of normalcy: ''I think we all have the potential for some behavior to become extreme— it's just that most of us have another behavior to counterbalance it. The idea [of health] I've been fiddling with—that certain behaviors balance out other behaviors in some complicated way—is an equilibrium concept." Health, as he construed it, was a function of balance between behaviors that were neither inherently good nor inherently bad. The potential to become addicted was not an aberration, we learned, but a liability that all humans carry."

By Natasha Dow Schüll

From Addiction Trajectories edited by Eugene Raikhel and William Garriott (Duke University Press, 2013)

Difficulty has long functioned as a keyword in poetics, music criticism, and, to a lesser...

Difficulty has long functioned as a keyword in poetics, music criticism, and, to a lesser extent, film studies. Technically, when a literary critic identifies a poem as difficult she makes no value judgment: the word is used to describe the poem's accessibility (not only in terms of comprehension but in terms of pleasure). "Poetic difficulty," writes John Vincent, "serves as a trace of drift or pulsion into the unmeaning, unknowable, and unspeakable. Much of the most exciting modern and contemporary poetry hovers at this edge, its lexical and affective power arising from unmappable, but somehow accessible, journeys out of and back into the known." A poem can be hard to understand — actively so — and still be very good and very moving. When we teach such works, we often begin discussion by asking students not "What does this poem mean?" but "What makes this poem hard to read?" and "Is it hard to understand, hard to enjoy — both?" The answers to these questions might be textual (a density of references), contextual (its rhetoric may seem strange to contemporary readers), narrative (characters with whom one can't relate), or interpretive (the work may in fact resist the effort to make sense of it).

Usually the critic's mandate is to resolve difficulty when we encounter it, to write as if that difficulty doesn't exist for us, even as we produce that difficulty as a noble, productive challenge, worth confronting and working through. Instead of erasing the labor of interpretation and instead of writing as if the critic's aim is to resolve difficulty, in Queer Lyrics: Difficulty and Closure in American Poetry Vincent imagines certain kinds of difficulties as deeply pleasurable and important, especially where they can't be resolved….

Vincent's approach to poetic difficulty leads the way for us, as art critics, to ask what people want from works like Mitchell's Death but also indicates the care one must take in order to avoid simplifying difficulty.

From Hold It Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art, by Jennifer Doyle (Duke University Press, 2013).

“The Nobel Prize-winning Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek, in an interview in the Yale...

“The Nobel Prize-winning Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek, in an interview in the Yale School of Drama journal Theater with her translator Gitta Honegger, describes how her male colleagues are allowed ‘to have this subjectivity, this precise, absolutely unmistakable gaze.’ This mode is ‘a way of talking,’ Ms. Jelinek continues, that ‘a woman, who is not considered a subject, simply can't have.’” - Elfriede Jelinek in Theater 36:2, made freely available, quoted in a New York Times Theater Review http://theater.nytimes.com/2013/03/11/theater/reviews/jackie-at-city-center.html

With Car Rental 8 you can discover affordable rental cars from over 50000 locations worldwide.

השבמחק